Lucian Freud: New Perspectives | National Gallery

Kindness isn’t a word that’s really associated with Lucian Freud, whose centenary retrospective is just coming to an end at the National Gallery. As befits such a big artistic beast - Freud has only become more mega-famous since his death in 2011 - the show is epic in scale. It’s loaded with the rather cruel portraits of his lovers and children he’s famous for: the early subjects bug-eyed and on the verge of tears, the later ones nude, uncomfortably contorted and rendered in thick oil paint.

The technique loosened over the years of course: the brushes got bigger and more loaded with paint, the layers on the canvas got thicker. But the discomfort of the subjects - squirming under the artist’s relentless, probing scrutiny - stayed the same.

But, here and there, Freud’s gaze becomes softer, empathetic, even kind. It’s not a coincidence that the things and people he paints in this mood are removed from the sexual marketplace in which he was such a brutally potent player. When working on flowers, dogs and landscapes, Freud’s brushstrokes tend to grow almost loving. The beautiful view of the Notting Hill roofs behind Two Irishmen in W11, for example. Or the sleepy whippet, poignantly unfinished, in his very last painting, Portrait of the Hound.

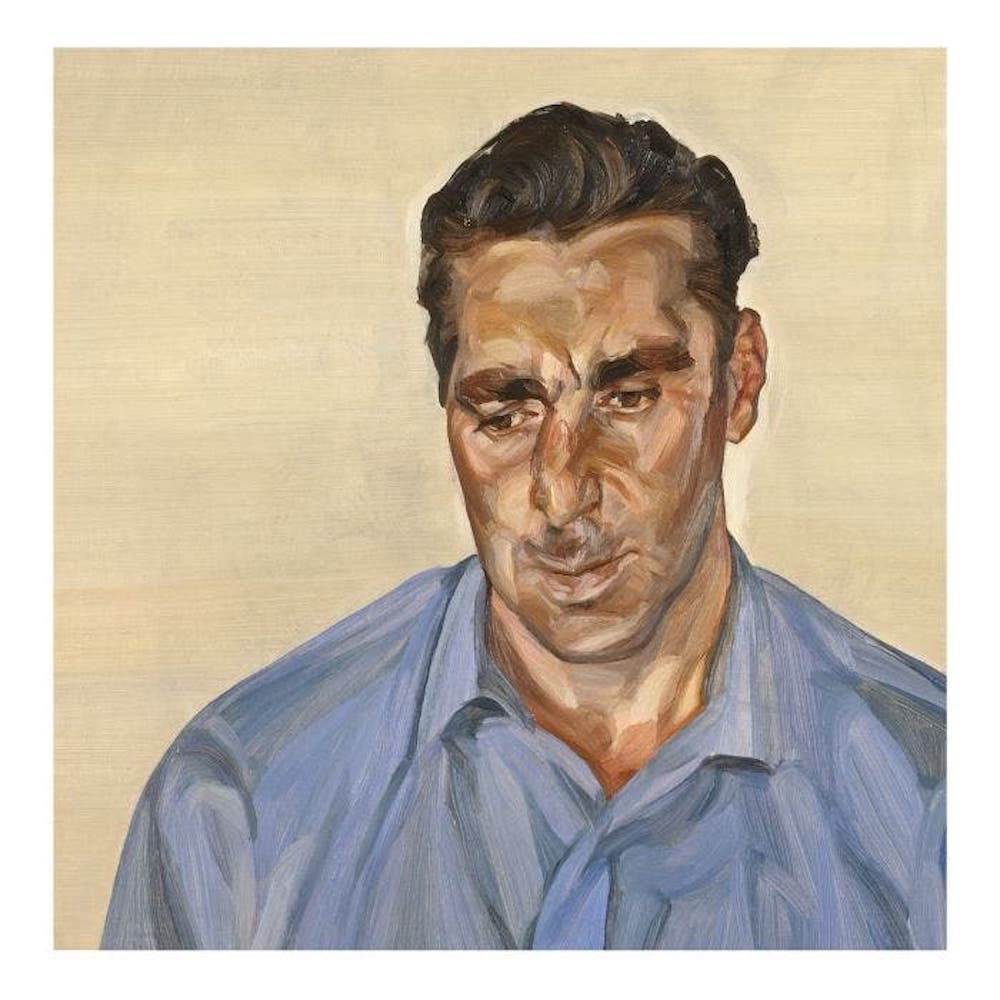

Gay men are objects of tender fascination for him. Freud had lots of gay friends, the most famous being Francis Bacon. And his portrait of Bacon’s lover George Dyer, Man in the Blue Shirt (above), is one of the show’s high points. I first saw this painting in a small exhibition at Ordovas a few years back, and then as now I’m struck by its kindness.

Dyer’s gaze is downcast, his broken boxer’s nose, strong jaw and lush quiff of hair carefully rendered. By contrast, Freud consistently zeroed in on the stringiness, the frizz and split ends of his female lovers’ hair. At the National Gallery show, there’s a particularly nasty portrait of Celia Paul from around the same time, right next to the one of Dyer. She looks in dire need of some Wash & Go.

Freud notices and highlights the man’s doubtfulness, his gentleness, despite his tough looks - looks which too-perfectly fit his background as an East End crook. Bacon, an energetic masochist, wanted Dyer to be rougher with him than he was. His lover couldn’t fulfil the fantasy, and felt bad about it. Dyer got his ultimate sad revenge by killing himself in Paris, on the eve of Bacon’s retrospective at the Grand Palais. Freud painted the portrait in 1965, seven years before that happened, but it’s impossible not to see something foreboding in this handsome man’s downcast glance.

Whatever you think of the great painter’s life or work, you can’t deny that Freud’s powers of observation never failed him. That he only occasionally turned these powers towards comfort, rather than cruelty, doesn’t lessen them. I wish he’d done it more though.

Lucian Freud: New Perspectives is at the National Gallery (London). 01 October 2022 - 22 January 2023